Annual Oration 1955

By Carl Bearse, M.D.

In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin wrote: "In 1751, Dr. Thomas Bond, a particular friend of mine, conceived the idea of establishing a hospital in Philadelphia... for the reception and cure of poor sick persons, whether inhabitants of the province or strangers." Thus was born the Pennsylvania Hospital, the first voluntary hospital in the United States. The seal chosen for the institution "bore a device of the Good Samaritan conveying the sick man to an inn, with the inscription `take care of him, and I will repay thee.'"

Those who contributed financially to this enterprise thereupon elected a board of managers. The Board not only chose the physicians who would practice in the new hospital, but passed on their "performance as practitioners." Though physicians were elected for terms of one year, the first three physicians "offered to serve the hospital for three years without compensation and to supply all the medicines for that time at their own expense." It is significant that when Dr. Thomas Bond was appointed to the medical staff, he resigned from the Board of Managers, on which he had served during the hospital's first year. This hospital therefore represents the oldest incorporated and surviving voluntary hospital in the United States and the establishment of principles that have more or less guided all future nonprofit hospitals.

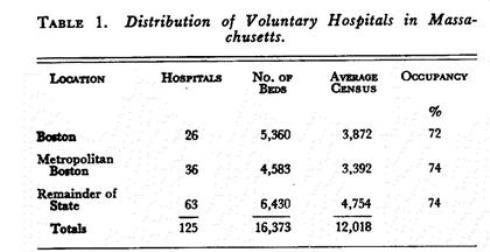

From this humble beginning has developed a gigantic hospital system, available to the rich as well as the poor. Today, hospitals are the sixth largest industry in the nation, and Massachusetts has more than its share of this industry. Facts and figures furnished by the Massachusetts Hospital Association reveal that there are 218 hospitals in Massachusetts. Of these, 125 — more than half — are nonprofit. The voluntary hospitals are distributed as shown in Table 1.

Since the preponderance of the population is in eastern Massachusetts and Boston itself is a renowned medical center, it is not surprising that half the hospitals and two thirds of the hospital beds are in Greater Boston. These hospitals employ altogether nearly 26,000 persons — more than 2 employees for every hospitalized patient.

The total assets of all hospitals in Massachusetts exceed $500,000,000; of this, $310,000,000 is in voluntary hospitals alone. The total annual hospital expense is almost $330,000,000, of which the share of the nonprofit hospitals is $100,000,000. But the most significant and disturbing fact of all is that the voluntary hospitals are now spending annually $3,000,000 more than their total income.

As far as the patient is concerned, the cost of hospitalization has risen almost to the point of diminishing returns. At the same time, hospitals are finding it necessary to reduce their capital assets to meet expenditures. It is evident that this situation cannot be permitted to continue too long.

The deteriorating financial situation in hospitals has been variously attributed to the economic depression of the 1930's, World War II, inflation and high taxes. The war forced hospitals to compete with high wages in industry. Before the war, hospital employees worked at standard salaries lower than those in other fields. Whereas wages then were only 40 per cent of hospital expenditures, today the figure is 60 to 65 per cent. In addition, many expensive new drugs have appeared, and the cost of food, surgical supplies and equipment has skyrocketed. Income from invested funds — Government subsidy, Community Chest, gifts and contributions — accounted for 11 per cent of total hospital income in 1952, as compared with 29 per cent in 1935. Since World War II, hospital charges have risen 161 per cent, in contrast to physicians' fees, which have gone up 45 per cent. Governing boards, which did such a superb job in building the nation's hospitals, have virtually ceased to be an adequate source of contributions.

Economies are, of course, being attempted. Hospitals have called in consultants to help simplify the operations of the various departments. Some nurses' training schools have been abolished. There is more group purchasing. Greater economies are undoubtedly possible. Are physicians perhaps ordering unnecessary laboratory procedures and wasting supplies? Are they discontinuing expensive drugs as soon as these drugs are no longer needed? Unfortunately, savings are possible only in the 35 to 40 per cent expended for supplies and upkeep. Salaries and wages, which account for the remainder of the expense dollar, cannot be reduced. With more than 1300 jobs unfilled, it is obvious that hospital employees are not overpaid.

Possibly, something can be learned from the management of proprietary hospitals. Generally speaking, their rates are about the same as those of the nonprofit hospitals, and patients are pleased with the services. Although proprietary hospitals are subject to taxation, I have been told by owners that they operate at a profit. To be sure, most of the patients have common ailments, and pay full rates. There is no teaching or research. On the other hand, should patients in voluntary hospitals be forced to underwrite prestige activities?

Principles of Payment for Hospital Care, a pamphlet published by the American Hospital Association (September 1953, page 8) declares that "Major expenditures... for medical research purposes... should... be financed from sources other than patients being served in a particular hospital."

Regarding teaching, the pamphlet comments: "Ideally, the cost of educating and training... should be financed by the whole community through a combination of public resources and private contributions, rather than by the sick patient representing a small percentage of the community, who is usually in the poorest position to meet such cost."

In consequence of all these developments, voluntary hospitals throughout the country are looking for new sources of income. Some apparently have been influenced by the propaganda that doctors make a great deal of money in hospitals and so should help meet hospital losses. However, both the American Medical Association and the American Hospital Association believe that the physician's role in hospital support should be that of any other citizen of like means.

Nevertheless, some hospitals have adopted plans for compelling staff physicians to pay for annual deficits incurred by the hospitals. One hospital "requested" staff members to make $1,000 "donations" to cover operating deficits. Another set up a compulsory plan for the collection of professional fees, the hospital to keep 50 per cent of the amount collected. Some hospitals require initiation fees of $150 to $500 for the privilege of becoming a staff member. One hospital was charged with placing the various services on the block — accepting bids for exclusive staff privileges. Some hospitals require the physician to pay for each patient admitted. Some employ full-time anesthesiologists, pathologists and roentgenologists, and make a profit on their services, even though this arrangement is contrary to law and the ethical principles laid down by the American Medical Association. Schemes such as legalizing bingo, lotteries like the ones operated in Mexico and annual sweep-stakes like those held in Ireland have also been considered on the assumption that as long as people like to gamble, the hospitals, too, might as well benefit. For example, in a History of the Massachusetts General Hospital by Nathaniel Bowditch the following item appears (page 53): "June 6 (1820) — The trustees declined applying to the legislature in aid of a project for a lottery, a portion of the profits of which were to be for the use of the hospital."

For years, voluntary hospitals in Massachusetts had partly subsidized industry and welfare departments by hospitalizing Workmen's Compensation and welfare cases at rates below those charged to the general public for comparable services. On December 1, 1948, however, insurance companies began paying hospitals on the basis of actual cost or what is charged to the general public, whichever is lower. As of January 1, 1955, hospitals are to be reimbursed on the same basis for the care of welfare cases.

The purchase of hospital services by agencies acting as a third party has necessitated improvements in hospital accounting. Since voluntary hospitals do not pay income taxes, their accounting methods have left something to be desired. Dr. Robert S. Myers, assistant director of the American College of Surgeons, wrote: "It would seem that hospitals are the only major business in which unreliable statistics are thoughtlessly selected, laboriously collected, promiscuously dissected, and unreservedly accepted as facts which accurately gauge achievements." In Massachusetts a new division of hospital costs and finances, in the Commission on Administration and Finance, has been in operation since January 1, 1954. Under the penalty provisions of Chapter 636 of the Acts of 1953, a hospital may be fined $500 for failure to provide such cost information as may be required. As a result hospitals are on the way to having a uniform system of accounting and cost analysis.

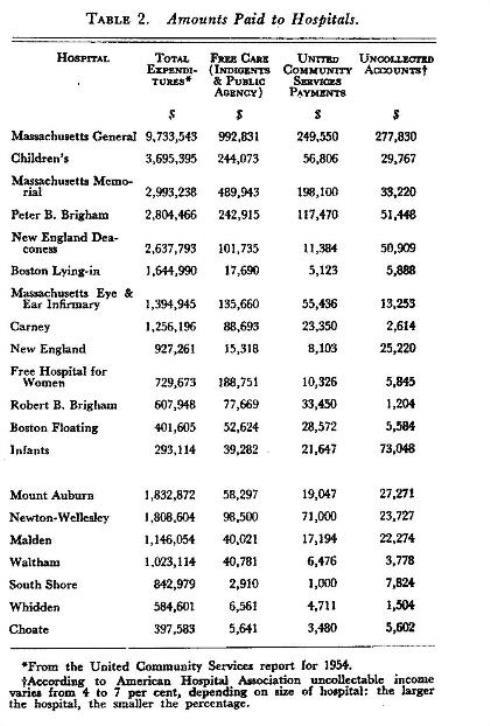

The Health Insurance Council reported that as of mid-November, 1954, 103,000,000 persons (approximately 62 per cent of the total population of the United States) had voluntary health insurance against hospital expenses. This includes more than 70 per cent (3,317,000) of the population in Massachusetts. Despite this encouraging fact there are still many patients who are unable to pay full hospital costs. Although most, if not all, of the nonprofit hospitals have funds earmarked to assist indigent patients admitted to their respective institutions, this money is no longer enough. Additional financial assistance is necessary. One such source is the Red Feather services. In the past, so far as the Boston Metropolitan Area was concerned, fund payments were based on operating deficits. Since 1951, however, payments have been limited to units of free service given to patients. The amounts paid to some of the hospitals in Metropolitan Boston, together with related information, are listed in Table 2.

Staff-Trustee Relations

Jerome Preston, president of the Board of Trustees of the Massachusetts Memorial Hospitals, has made the following comment on this most vital aspect of hospital administration:

A hospital is unique among institutions in that staff doctors are independent of it and have no responsibility for its finances. Their professional responsibility toward the patient, like the financial responsibility of the trustee toward the donor, cannot be delegated. Such a division of responsibility is an organizational monstrosity, one that has troubled both doctors and trustees for years.

In addition, hospital income now comes largely from the staff's private patients. This combination of factors has created a definite impairment of staff-trustee relations.

The House of Delegates of the American Medical Association has taken cognizance of this schism. In December, 1951, it approved a report pointing out that "Since the physician and hospital are interdependent, it is incumbent on both to be interested in all phases of their scientific and financial relationship."

Eighteen months later the House of Delegates approved another report that commended the people who serve on governing boards and added:

They are not necessarily particularly informed as to the many intricate problems involved in the production of good medical care.... If they have opinions on critical matters [these opinions] are likely to be gained from the personal advisor or by casual contacts at social gatherings or on the golf course.

Various methods were recommended by which the medical staff could have "free and direct access to the governing board." Of special interest is the recommendation that members of the medical staff serve on the governing board.

Regarding this recommendation, the Detroit Medical News, on October 26, 1953, made the following editorial comment:

An agreement to accept physicians as members of Boards of Trustees of hospitals has been reached.... The formation of a partnership by the staff of a hospital and its trustees... augurs well.

In the opinion of Dr. Malcolm T. MacEachern, director of professional relations of the American Hospital Association, the policy of having the medical staff represented on the governing body is not in accordance with the principles advocated by the American Hospital Association. Some of the reasons advanced are that membership on the governing board gives undue publicity to the individual physician; that he may use his position to promote himself on the staff; that the staff may come to regard him in the light of an inspector; that he may exert his authority in the employment of hospital personnel; and that finances and business are foreign to him.

Granting that all objections to having physicians on governing boards are valid, how much better qualified are the laymen to serve as hospital trustees? In 1952, Raymond P. Sloan, for many years a hospital trustee and editor of The Modern Hospital, wrote a book, This Business of Ours. The book, described as "A Guide Book for Hospital Trustees, Hospital Workers and Laymen," has this to say:

Although some parallel can fairly be drawn between hospital operations and that of big business, there is a point at which marked divergencies will be noted. The industrial organization is governed by those who supposedly know their fields; the hospital organization is governed by men and women who have little, if any, knowledge of its professional affairs.... [The doctor] sees a layman possessing little acquaintance with medical science or hospital technique... placed in a position where he dictates policies and exerts controls over those who have spent years in acquiring professional knowledge. What could be more inconsistent?

The director of the Doctors Hospital in Seattle (Dr. Robert F. Brown) believes that more is to be gained than lost by having physicians serve as trustees. In the opinion of many hospital administrators, according to Dr. Brown, physician trustees foster better understanding between the medical staff and the board. Although nonmedical boards become more easily a rubber stamp in approving candidates for staff appointment, physician trustees are more inclined to evaluate applicants on their credentials. He refutes the criticism that physicians are lacking in business ability by pointing out that they serve as trustees of universities and research foundations, on the corporate boards of industry and in the insurance field.

Dr. Frank H. Lahey, in his presidential address before the New England Surgical Society on September 10, 1932, spoke as follows:

I believe that on every hospital staff there should be several members of the staff who are trustees of the hospital;... if the members of the medical profession do not assert an interest in and accept a responsibility for their economic management, they, the medical men, will be pushed farther and farther down the scale until they assume the position from which they are now not far distant, of "hired men," more or less — under the power and control of trustees and superintendents.

The set-up of the Massachusetts Blue Shield Corporation could well be used as a pattern for hospital governing boards. Of Blue Shield's members, one is a banker, represent labor and industry, and 5, or a third, are physicians. Thus, Blue Shield has broad public and medical representation. On hospital governing boards at least 3 physician trustees, with staggered terms, should be elected by the staff. It would be well, too, if these physicians were not permitted to succeed themselves. This system would over the years permit a large percentage of the staff to serve on the governing board and to become better informed of trustees' problems. It would also implement the recommendation of the House of Delegates of the American Medical Association that "every professional man on the appointed staff have a voice in the professional management of the institution."

Regional Integration

Another aspect of the problem facing the voluntary hospital that deserves serious consideration is regional integration. In a way, voluntary hospitals are engaged in a highly competitive enterprise, even though they are erected in the public interest, are exempt from taxation, receive funds from philanthropic-minded individuals and agencies, and may even be assisted by federal and other tax funds. They are in competition not only with hospitals entirely supported by taxation but also with one another. They compete for funds; medical, nursing, and technical personnel; prestige; and even for patients. Since all nonprofit hospitals are dependent on the beneficence of the public, their attitude toward one another should be Cooperative rather than competitive. This competition exists not only among hospitals located in a single city but also between urban and suburban hospitals. Increased occupancy of community hospitals results in decreased occupancy of city institutions.

What the Hoover Commission had to say about the various federal medical systems can well be applied to voluntary hospitals: "They go their own ways, make their own plans, build, staff, and run hospitals and clinics with little knowledge of and no regard for the operation of others." Voluntary hospitals, finding themselves with a high average census, have embarked on building programs even though there are empty beds in nearby institutions. Under the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, construction costs in Massachusetts during the past five years have averaged over $17,500 a bed. If hospital needs were considered on a regional rather than on an individual basis, overlapping facilities would be avoided, and substantial savings would result. Less busy hospitals would benefit, for the more closely the average occupancy of a hospital approaches 100 per cent, the lower the unit of cost of medical care.

One may ask how effective integration can be accomplished. Here are a number of recommendations by the American Hospital Association Commission on Financing of Hospital Care: regular meetings for discussion of common problems; joint recruitment of nurses; sharing of skilled personnel; joint purchasing and joint collections; joint reporting of operating data; agreement to treat certain types of cases and to provide particular services in specified hospitals; and merger of hospitals when it is in the interest of effectiveness and economy.

Since most, if not all, of the hospitals in Greater Boston belong to the Boston Hospital Council, this agency could well serve as a medium for discussion of mutual problems in this area. Similar councils, to operate in the same manner, could be organized in other sections of Massachusetts. Due consideration should be given, of course, to overlapping regions. Possibly, the Massachusetts Hospital Association could undertake the over-all job of founding these regional councils.

The United Community Services of the Metropolitan Boston Area has become interested in this problem. It has obtained a grant of $125,000 from the United States Public Health Service for a three-year basic research project to evaluate improvements that may result from regional co-ordination in an urban area.

To be truly effective, the integration of hospitals within an area, as I see it, would require an interchange between co-operating hospitals of courtesy-staff privileges for the care of private patients. Before integration, hospitals should be approved by the Joint Committee on Accreditation. In this way, the qualifications of staff members would meet the standards of all co-operating hospitals. No change should be made in the closed-staff setup for the care of service cases. I might observe at this point that integration has been tried in some communities and has been found to work very well.

With integration and reciprocal staff relations in effect, patients will be able to have free choice of physician. At present they can only be sure of "free choice" when services are rendered at home or in the office, for, if the patient insists on a hospital where his physician is not a staff member, he must give up either his physician or the hospital of his own choice.

A clergyman made the following observation:

And speaking of hospitals here is another source of misunderstandings and ill will. The doctor wants to head off socialized medicine. One of the arguments he uses is that the patient should be free to choose his physician.... But often the doctor does not practice what he preaches and [does not allow] his patient freedom to choose the hospital he wants to enter, but insists — to the point of breaking the patient-doctor relationship —on the hospital of the doctor's choice.

Unfortunately, the minister quoted appears to have overlooked the doctor's dilemma — that sometimes the hospital of the patient's choice is one in which the doctor does not have staff privileges!

Much more to the point is an editorial in the Bulletin of the Columbus (Ohio) Academy of Medicine (March, 1953) proposing that every member of the Academy be given courtesy-staff membership in every hospital in Columbus. It asks a pertinent question:

By what specious reasoning do we decide that a certain doctor can use the facilities of some hospitals, but not others? Such decisions are apparently based less on professional considerations than... on the whims or personal prejudices of those entrusted with the decisions.

Under the present system, the staff physician's freedom of choice is also restricted. He may have as consultants only members of the staff of the particular hospital to which his patient has been admitted. With integration of hospitals on a regional basis and interchange of staff privileges, both physicians and patients will be better served. Physicians will have unrestricted free choice of consultants and patients will achieve free choice of physician and free choice of hospital.

With regional integration some hospitals could be reserved for routine cases. These hospitals would not have to be so elaborately equipped and staffed as institutions reserved for patients who require more intensive study and more complicated procedures. There would thus be less duplication of services and equipment. Since fewer technicians would be necessary, there would be a saving in salaries.

If a patient in one hospital required the facilities of a more elaborately equipped hospital, he could be transferred there and yet remain under the care of the original physician. Last but not least, the patient would save. The patient with a routine illness would no longer be charged for a share of the cost and technical servicing of equipment rarely used.

The larger, better known and busier hospitals that are not interested in pooling their facilities with more modest institutions should bear in mind the value of integration in times of disaster such as fire or war. Any voluntary hospital contributing to the difficulties of other voluntary hospitals may be contributing to the breakdown of the whole voluntary system.

When there is actually a need for new hospital construction, consideration should be given to institutions in which some floors are used as a hospital and other floors as a hotel. Such an arrangement would shorten the stay of the patient in the hospital section and reduce the costs of hospitalization.

Another method of cutting the high costs of hospital construction and equipment would be to increase the use of existing facilities. It has been pointed out that the elimination of week ends and holidays would increase hospital capacity by about a third.

Virtually the same thing was said by the president of the American Medical Association who suggested that "making hospital services available on a full week or at least a six-day basis, rather than the present four-and-a-half to five-day utilization, would not only reduce the cost of the care of the individual but would lessen the number of hospital beds needed to service a community."

Another physician, this time a patient, wrote as follows:

At 4:30 P.M. on Friday I was taken to the hospital, presumably with a kidney stone. X-rays were in order, of course, and some kidney function tests.

But the laboratory operates on a five-day week. From 4 P.M. Friday to 8 A.M. Monday, nobody is there... So I just lay around all week-end, waiting for the technicians to come back.

It's obvious that the forty-hour week in a hospital is as much a bane to patients as it's a boon to employes....

The hospital keeps its switchboard going twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. I suggest that it could keep all departments open on Saturday and Sunday, 8 A.M. to 4 P.M. Even though this would cost more in overtime salaries, the increment would not be a very big item in the total budget. And the returns would be tremendous.

Look magazine (August 24, 1954) took note of one ingenious attempt to solve this problem of the "lost week end" in hospitals: "Week-end patients," the news item read, "are being welcomed at San Francisco's Mt. Zion Hospital. To take up Saturday and Sunday slack, the hospital is seeking patients from among overworked folk who need a check-up and could use two days' rest."

Finally, the Committee on Financing Hospital Care warned that "Overbuilding, in the attendant failure to make full use of bed capacity and diagnostic and therapeutic facilities, should be avoided." It recommended "reducing seasonal and week-end lulls whenever practicable, and making diagnostic services available at all times." It also advised programs for making preventive medical care available at a reasonable cost to all groups in the population.

Audits

The desirability of self-audits by hospital trustees merits consideration.

The Joint Committee on Accreditation of Hospitals requires that the quality of professional work in a hospital be under constant examination by the staff. Meetings must be held at least monthly for the purpose of reviewing the medical care of patients within the hospital.

It seems only proper that the work of the governing board should be subjected to a similar self-audit and individual members made answerable for their functions just as physicians are for the care of patients. Here are some pertinent questions that might be asked at one of these governing-board audits: Are the trustees receiving sound and unbiased advice from impartial physicians? Is the work of the administrator being adequately supervised? Are there lapses in hospital-physician and in hospital-public relations? How successful are the money-raising activities? How well are individual trustees attending board meetings? How well are they carrying out their committee assignments?

When Benjamin Franklin was unable to get the board members of the Pennsylvania Hospital to meetings on schedule, he had the following resolution passed: "[that] each member is to pay two shillings sixpence for total absence and one shilling for not coming on time, and for every hour's absence after the fixed time, sixpence per hour, all of which fines to be disposed of as the majority may direct. The town clock, or should that not strike, the watch of the oldest person present to be the standard for determining the time."

The governing board, like the medical staff, should make every effort to disclose its own weaknesses and errors, and to correct them. If anything, the work of the trustees should be checked even more carefully than the work of the professional staff. Physicians, at least, are trained for their jobs, whereas the individual lay trustee assumes a responsibility for the conduct of a public utility about which he usually knows very little. So much for the trustees. May they find these suggestions helpful!

New Era in Hospital-Physician Relations

In June, 1950, the House of Delegates of the American Medical Association recommended that committees on hospital and professional relations be created on state and county levels. These committees were to receive complaints from any physician, hospital, medical organization or other interested person or group about professional or economic relations existing between physicians and hospitals. Such committees were appointed by the Massachusetts Medical Society and the district medical societies.

A further step in the improvement of hospital-physician relations was taken a year ago by the Council of the Massachusetts Medical Society and the trustees of the Massachusetts Hospital Association. In short, the two organizations agreed that no governing board should deprive a physician of staff membership or reappointment, or change his privileges in any way without informing him of the charges against him and without previous consideration by the staff; that on request a review should be made by a committee with equal representation from the staff and governing board; that if this committee was unable to make a majority recommendation, or if any of the parties involved so desired, a request for an opinion should be made to the presidents of the Society and the Association; that, on receipt of such request, the president of the Society should appoint 3 members of the Society, and the president of the Association 1 hospital administrator and 2 hospital trustees to act as an appeal board; that the 6 appointed members should select a lay chairman; and that the findings of the various committees should be transmitted to all the parties involved.

The Norfolk Medical News, in a subsequent editorial (November, 1954), reported as follows:

As a result of this cooperative action between the M.M.S. and M.H.A., staff members who feel they have been unjustly treated now have a court of appeal. These procedures, of course, carry no legal force, and are not binding on the governing boards of hospitals. However, the moral effect on hospitals belonging to the M.H.A. (and practically all belong) will be to induce these institutions to abide by the recommendations.

Future

The most vital question at present is the outlook for the voluntary hospital. In The Hospital in Contemporary Life (1949) Dr. Nathaniel W. Faxon wrote as follows: "What shall we do now? Confronted with the necessity of meeting hospital costs — and they must be met, some people are suggesting the common solution, turning it over to the government."

Evidence of the extent to which the federal Government has gone to the assistance of the voluntary-hospital system appears in the report of Dr. A. Daniel Rubenstein. Since 1948, under Public Law 725, $13,990,190 has been allocated to 58 projects in Massachusetts for hospital and health-center construction. Of this, 79 per cent ($11,052,250) went to general hospitals, including teaching hospitals, maternity hospitals and laboratories; 3671 beds and 602 bassinets were added.

Fortunately for the voluntary-hospital system, "there were," in Dr. Rubenstein's words, "no federal controls. Hospitals aided under the program have maintained absolute freedom of action." But if governmental aid continues to be accepted, will the freedom of physician and hospital remain unimpaired?

Some hospital administrators, faced with continuing deficits, would have little or no hesitancy in placing their institutions, as Dr. T. F. Laye puts it, "in a government socialistic noose." But it is fair to say that this practice would not meet with the overwhelming endorsement of the medical profession.

A somewhat gloomy view of the future of the voluntary hospital has been taken by the trustees of the Massachusetts General Hospital, which, in its 1953 report (pages 42–43), observed that "For the first time since 1936 the overall operations of the hospital did not end in a deficit. There is nothing in the present outlook to indicate that deficit years will be less frequent in the future than in the past."

On the other hand, MacEachern appears to be optimistic regarding the future of the voluntary-hospital system. "I feel," he says "[that] the voluntary hospital is here to stay. It tends more and more to give higher standards of service, eliminates ‘routinism’ and retains certain humanitarian characteristics, more so than a government institution."

In general, however, the outlook for the community hospital appears to be better than that of the metropolitan hospital. Factors favoring the community institution are its convenience, civic pride and the availability of well trained men who have settled in the community. Some local hospitals are even being modeled after the university hospital. Also, since the community hospital may be the only hospital in its area, it receives from the public as well as from the staff physicians proportionally greater support than urban hospitals. Last year the Beverly Hospital put on a campaign. As of December 30, 1954, $625,000 had been subscribed by the public. In Fitchburg, $1,192,000 was raised by public subscription. The 48 members of the staff alone contributed $115,000. Of more than $600,000 raised by the Maiden Hospital, exclusive of an additional single donation of $100,000, 96 physicians contributed $105,000, and of the $428,000 contributed by the public to the South Shore Hospital, $75,000 came from the staff.

Other straws in the wind indicate that the voluntary hospital promises to continue more or less unfettered for some time to come. On Long Island, New York, there is a labor-management coalition, formed to aid voluntary hospitals. At the end of four years the fund had reached $1,000,000. Last year, Indianapolis refused federal hospital funds but raised $12,000,000 locally.

In this connection I cannot help observing once again that the circumstances attending the founding of the Pennsylvania Hospital seem peculiarly apropos to the problems that the voluntary hospital faces today. Franklin writes as follows in his Autobiography:

The proposal [i.e., the founding of a voluntary hospital] being a novelty in America, and at first not well understood [Dr. Thomas Bond] met with but little success... I inquired into the nature and the utility of the scheme, and receiving a very satisfactory explanation, I not only subscribed to it myself, but enlarged heartily in the design of procuring subscriptions from others. Previously, however, to the solicitation, I prepared the minds of the people by writing on the subject in the newspapers, which was my usual custom in such cases, but which he had omitted.

Since governmental assistance was also wanted, and the Assembly appeared not too enthusiastic about the idea of a hospital, Franklin proposed a petition to the Assembly for public aid and devised a scheme for matching contributions by the Government and the public. In Franklin's words: "This condition carried the bill through."

It will be recalled that the first physicians of the Pennsylvania Hospital agreed to donate the necessary medicines in addition to their services. But "their generosity was not called on for long as the Managers soon undertook this financial burden." In the hospital minutes of December, 1752, the following note appears: Agreed that the Managers, each of them in Turn, solicit Subscriptions from the rich Widows and other Single Women in Town, in order to raise a Fund to pay for the Drugs."

A benefit performance given in 1759 cleared more than £47 for the hospital. In 1764 an eloquent minister preached a benefit sermon that yielded over £174 including a personal contribution of £5 from the orator. Charity boxes were distributed in various places, and by 1846 had yielded $19,093.44.

Over the years, voluntary hospitals have not only continued to use the money-raising technics of the Pennsylvania Hospital, but have improved upon them. And yet the problem of hospital financing is still serious.

The Commission on Financing Hospital Care has acknowledged that voluntary prepayment is the backbone of hospital income, and that the financial stability of the voluntary hospital is increasingly dependent on this source of income. But the Commission believes that a danger is inherent in prepayment — that "it may encourage unnecessary utilization of hospital services and weaken or remove incentives to minimizing hospital expenditures." This, in turn, would increase the cost of such insurance to the subscriber. The Commission recommended:

1. Continuing programs of education to make the public more aware of its need to budget for hospital care by the purchase of prepayment insurance.

2. Encouragement of more employer participation in the cost of prepaid protection for employees and their families.

3. The development of methods to enroll, under prepayment plans, dependents, the self-employed, domestics, farmers, those retired under pension plans, the unemployed, and migratory workers.

4. That hospitals make greater efforts to obtain additional support from individual communities, corporations, and foundations. And that (if governmental help is necessary), federal assistance should be sought only when the state is unable to help.

5. That medical schools and hospitals should accept responsibility for educating physicians and other responsible personnel in hospital economics in an effort to eliminate waste of facilities and supplies.

In connection with the last recommendation, Miss Carolyn K. Winters, administrator of the New England Hospital, believes that everyone connected with a hospital should also be educated in good public relations. This need was emphasized in an editorial that appeared in the Boston Herald ("Humanizing the Hospitals," January 11, 1955):

The average hospital today needs a lot of humanizing.... It seems both fair and wise that we who support the hospitals should share also in their day-by-day existence, that we should feel a sense of common purpose with them. We can't if they are aloof.

The 1949 interim report of the New York Hospital Study, directed by Dr. Eli Ginzberg, of Columbia University, predicted that hospitals will face additional financial difficulties: "Hard times, if they come, may force the opening of hospitals to all doctors of a community on an equal basis in order to fill empty beds." The report further emphasized the fact that the best possible service cannot be provided for the public if doctors without staff appointments are refused beds on the grounds that only certain doctors are entitled to a preference in the hospitalization of their patients. In any long-range planning, the report continues, the liberalization of the present, closed "gentlemen's club" system of staff membership should play an important part.

The Massachusetts Medical Society has made a forthright and enlightened effort to do just what the New York Hospital Study recommends by sponsoring what has been called the Gallupe Plan, under which graduates of unapproved medical schools who have no staff privileges in approved hospitals are given an opportunity to practice in hospitals under the supervision of staff physicians. When they are found to be qualified, staff appointments should follow. Where this plan has been put into effect it has worked satisfactorily. A general acceptance of the Gallupe Plan would increase the proficiency of the physicians affected and gain their good will and that of their patients.

Conclusions

My own opinions concerning the voluntary hospitals (which have been liberally enriched by others!) should by now be fairly apparent. Even so, it might be well for clarity's sake, briefly to review them here.

The public, which has already demonstrated its willingness to support the voluntary hospital, should be further acquainted with hospital problems and the need for greater financial assistance.

Every effort should be made by the profession to encourage the expansion of prepayment health insurance, including employer participation.

Staff physicians should concern themselves with the administrative and financial problems of hospitals. "Medical economic auditing" by the staff, for example, may disclose methods by which economies would be possible.

Staff representation on governing boards would make for closer co-operation between staff and trustees.

The cost of hospitalization to the patient should be kept as low as is consistent with the best possible care. This can be accomplished by financing research and teaching from sources other than the patient; integration of hospitals on a regional basis; and utilization of hospital facilities on a basis of six or seven days a week.

The standard of medical practice would be raised and public relations improved by liberalizing staff appointments. The public is entitled to free choice of hospitals as well as of physicians. As American Medical Association President Walter B. Martin has said so well, "Medicine belongs to the people. We are merely its purveyors."

Since the voluntary hospital is an indispensable medium by which the medical profession renders service to the public, its problems must continue to receive the persevering support of both the public and the profession. As one of my favorite sources, Benjamin Franklin, has observed: "Diligence is the Mother of Good Luck. And God gives all things to Industry."

_______________

Bearse, Carl. "The Involuntary Plight of the Voluntary Hospital." New England Journal of Medicine 252, no. 20 (1955): 829-36.

View all Annual Orations